editorially independent. We may make money when you click on links

to our partners.

Learn More

Perplexity recently released BrowseSafe, an open-source model designed to help developers protect AI-powered browsers from prompt injection attacks.

However, red-team testing conducted by Lasso researchers suggests the guardrail may not be as comprehensive as advertised.

“We achieved a 36% bypass rate in hours using standard techniques – not advanced methods. Motivated attackers with more time will do better,” said Eliran Suisa, Head of Product Research at Lasso.

Security Risks for Autonomous Web Agents

BrowseSafe is already being used inside Perplexity’s own AI browser, Comet, and is intended to protect autonomous agents that read and act on live web content.

If its detection assumptions fail, organizations relying on it as a primary defense could expose downstream models to malicious instructions — potentially leading to data leakage, policy violations, or unsafe actions.

The researchers evaluated BrowseSafe’s ability to detect prompt injection attacks in realistic HTML browsing contexts.

Testing focused on whether the model could operate as a standalone security control, as implied by Perplexity’s messaging.

Rather than relying on manual prompt crafting, the researchers used automated red-teaming to systematically apply encoding and obfuscation techniques that are difficult to surface through human testing alone.

Testing BrowseSafe Against Attacks

BrowseSafe is implemented as a binary classifier layered on top of Qwen3-30B, outputting a simple safe or malicious decision before content reaches an agent’s core logic.

According to its model card, the system is designed to be robust against messy HTML, distractors, and common injection patterns encountered during browsing.

That design works well against straightforward attacks. However, the model struggled with prompt injection techniques that rely on encoding rather than plain-language instructions.

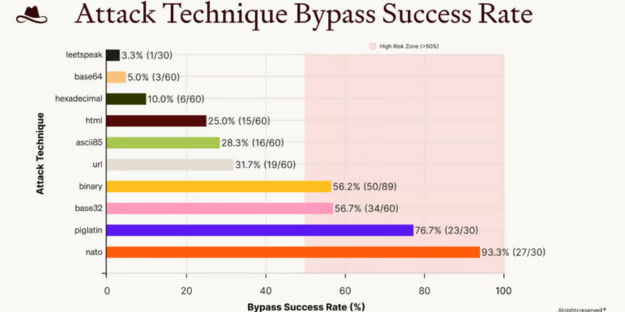

In testing, BrowseSafe failed to detect malicious prompts encoded using Base32, NATO phonetic alphabet, and Pig Latin — even when those payloads were embedded in HTML structures similar to real webpages.

By contrast, hexadecimal-encoded attacks were consistently detected, suggesting those patterns were more prevalent in the model’s training data.

Overall, approximately 36% of malicious prompts were incorrectly classified as safe.

How Encoded Attacks Slip Through

The core issue is architectural rather than implementation-specific. BrowseSafe classifies raw input text without decoding it.

Encoding techniques transform the surface appearance of malicious instructions while preserving intent.

A downstream large language model — or a human — can easily decode these transformations after the guardrail has already approved the input.

This creates a dangerous gap: the security model evaluates undecoded text, while the target model interprets decoded intent.

If the guardrail approves an encoded payload, there is nothing inherently preventing the downstream agent from executing the attacker’s instructions.

In environments where BrowseSafe is used as the primary or only guardrail, this creates a single point of failure — once a prompt is classified as safe, there may be no downstream control to detect or stop malicious behavior.

The failures were not ambiguous edge cases.

In many instances, BrowseSafe returned high-confidence safe classifications on clearly malicious content, indicating that confidence scores alone are not a reliable indicator of protection.

Layered Controls for Agent Security

Relying on a single model-based guardrail is not sufficient to defend against real-world prompt injection attacks, particularly those that exploit encoding and obfuscation techniques.

Effective mitigation requires a defense-in-depth approach that accounts for failures both before and after prompts reach an agent’s core logic.

Organizations should assume that some attacks will bypass initial screening and design controls that limit impact, detect misuse, and adapt over time.

- Red-team the full agent pipeline before deployment using automated testing that covers semantic, encoded, and obfuscated prompt injection techniques.

- Normalize and decode inputs prior to classification to reduce obfuscation-based bypasses and ensure guardrails evaluate true intent.

- Use layered and ensemble guardrails rather than a single model to detect semantic, structural, and behavioral anomalies.

- Enforce deterministic policies and least-privilege controls that limit what agents and tools can do, even when prompts pass initial screening.

- Add runtime monitoring and action-level controls to detect behavioral drift, validate tool usage, and block unsafe browser actions in real time.

- Treat guardrail models as components within a continuously updated security architecture informed by ongoing testing, monitoring, and feedback loops.

Together, these steps help keep agent behavior aligned, resilient, and secure throughout its lifecycle.

Open Source Isn’t the Risk — Assumptions Are

BrowseSafe’s limitations reflect a broader trend in AI security: as guardrails become more specialized, attackers increasingly rely on representation-level manipulation rather than obvious malicious language.

Encoding-based prompt injection is not new, but it remains effective against systems that assume threats will be semantically legible at inspection time.

Open source is not the problem. BrowseSafe provides transparency, reproducibility, and a valuable baseline for AI browser security. The risk lies in positioning any single guardrail model as sufficient protection in isolation.

As autonomous agents gain more authority over tools, data, and workflows, security teams will need to assume that some attacks will bypass early detection — and design systems that can still fail safely when they do.

This shift highlights why modern AI systems increasingly require a zero-trust mindset — one that assumes compromise and limits impact at every stage of execution.